RATED “EXCEPTIONAL,” representing the top 10% of new

books published each year in America — TODAYS BOOKS, 2003

ISBN 978-0-9798236-1-9; Reissue 2009

Library of Congress # 2002110706

Originally Published 2002

Paperback Original; 457 pgs. $18

Now Still Available through the Author

- For those interested in: Art, Mental Illness, Women’s Issues, Biography, Cultural Studies, Humanities, the Literary Tradition, Greenwich Village, Abstract Expressionism, FDR’s WPA Programs, Work-Life Philosophies, Social Policy and Self-Improvement

- Educators, Civic Leaders

- Librarians, Archivists

- Historians

- Therapists

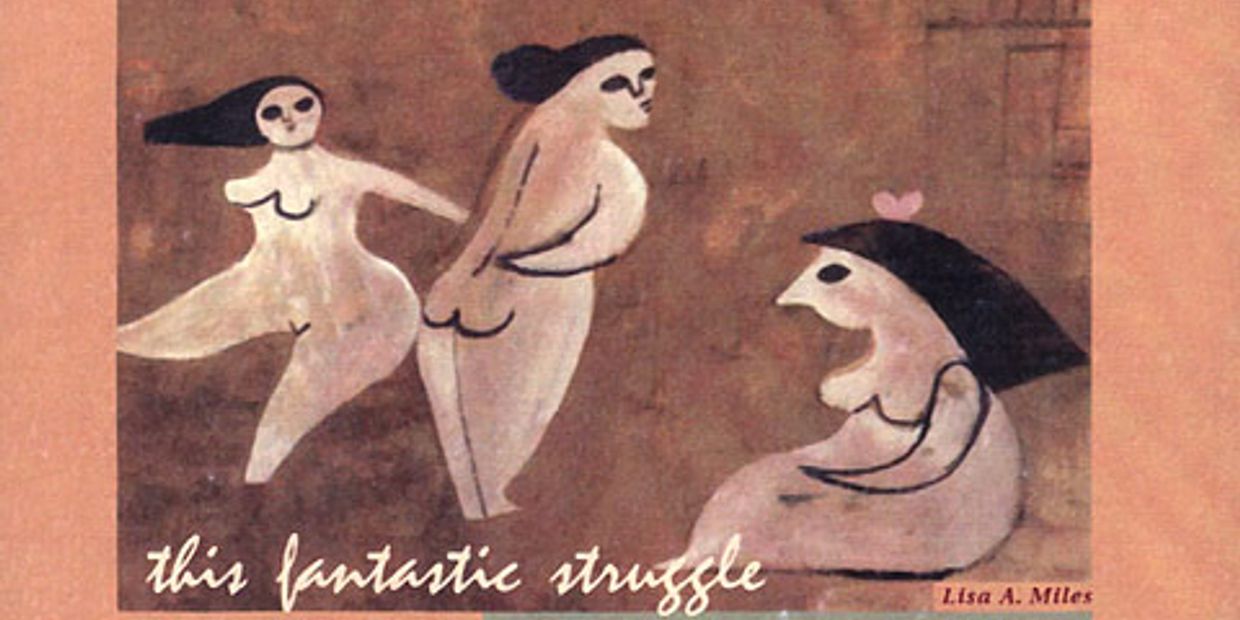

- Uniquely woven together with scholarly source material,“interviews of aging bohemians,” mental institution documents, reproduced graphics from 1920s reviews and hand-scrawled letters, & a beautiful color-plate middle gallery of Esther’s paintings

- Both a colorful Biography & relevant Cultural Essay

- A fascinating story & absorbing limpse at what it really means to be an artist

- A heartwarming story of friendship sustained by the power of a now-extinct literary tradition– keeping alive not just friends over distance & illness, but art work otherwise lost to the world

- A creatively-layered design of a life, and life-affirming tale of a woman who lived poor but died saying hers was the most wonderful possible life– prompting all to better understand their own passions and self-direction

Praise for This Fantastic Sruggle: The Life & Art of Esther Phillips

“A meticulously detailed biography of little-known 20th century artist Phillips. Miles records the struggle (including institutionalization) of an artist wholly committed to her craft [and] offers the life of her subject as an emblem of the hardships and inner passions in the lives and careers of other artists…. Miles’ celebration of Philips will stand as a thoughtful and compassionate contribution to the study of artists laboring on the margins. Recommended. Faculty and Researchers.” -B.L. Herman, University of Delaware, CHOICE Magazine.

“A remarkable book…both educational and provocative. [It] will arouse attention.” -Robert Henkes, author, American Women Painters of the 30s & 40s.

“The story of one who produced so much art, yet left so many questions… I couldn’t stop reading! -Brian Butko, Editor, Western Pennsylvania History Magazine.

“Miles is the most great-hearted biographer of a cantankerous artist since Irving Stone wrote of Van Gogh. May Swenson would have loved again meeting her friend Esther Phillips in these pages.” -R.R. Knudson, author, The Amazing Pen of May Swenson.

“Most inviting–so well done graphically. The book is artistic and intimate in its design.” -Louise Sturgess, Director, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

“This book has a unique flow that is missing from many of the other biographies I have read. I would definitely recommend it.” –Aug 2010 Bridget H., Readaholic Blog

“A tribute . . . to all artists who struggle. [A] much needed book.” – J. Kevin McMahon, President, The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust.

“Intricate and insightful, filled with drama and facts… a comprehensive coverage of a lesser-known artist who deserves a place in history.”

-The Bookwatch, 2002

Abstract

This Fantastic Struggle: The Life and Art of Esther Phillips depicts a woman who endured much hardship, including institutionalization, just so that she could pursue a life of painting. It is indeed a biography, but also the tale of many forgotten artists, throughout history, and working unto this day. Woven together with letters, interviews, scholarly source material, art work, and institution documents acquired upon author’s petition for their Court Ordered release, the book becomes a unique cultural essay.

Esther Phillips made Greenwich Village her home in 1936, she then in her mid-thirties. She never returned to her hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but what would surface was pieces of her story, making themselves known through decades of correspondence and speculation among friends, as well as through her paintings, which did come back. In the Village, Esther lived very minimally, but very committed to a way of artistic life. Upon falling ill, she was institutionalized for over six years in the small town of Wingdale, in eastern New York. There she would commence the prolific painting activities that would always make up her life, producing canvases that portrayed her otherworldly existence at the time. And upon her release, returning to the transient living in the harbor that was the Village, she once again attempted to cope with a larger society that did not recognize her efforts.

Esther’s story is told through innumerable primary source documents and dialogues, and of course, her work, which is shown extensively throughout. There are letters between Esther and Pittsburgh woman writer Merle Hoyleman, not only a dear friend, but an agent of sorts for her art. The devotion and diligence she expended as both is startlingly apparent in letters to Esther and to those she successfully marketed to, and also in scores of journals that reveal the intensity of her own creative life. The effects of fellow Village artist Eugenia Hughes, all fourteen boxes of which sit codified in storage of the New York Public Library, illustrate another remarkable bond of friendship that survived adversity. They spin a tale in themselves, and testify to the strong literary tradition of earlier times. Perhaps the greatest find among them–which includes everything from actual art work of Esther and “Jerry,” source material on the famed personalities of the Village, and diaries galore–are original copies of letters Esther wrote while institutionalized. “I felt a vague, strange, and then real impulse to write you–knowing or rather remembering that you had written to the doctor. I still feel almost no hope for myself…but what I want Jerry is this–my watercolor box & 2 good brushes….”

The voice of our main character surfaces as well out of transcriptions of visits that a niece took almost upon Esther’s death bed. Esther gave entertaining portraits of the lascivious Village, and a peek into the inner-relationships among the lucky few who would reach fame as Abstract Expressionists, and those who did not, as most of the rest of the Village artists. Her few poignant reflections, echoed by all who knew her, were almost lost among her many humorous anecdotes. “I did exactly what I wanted in my life…I was happy I could paint.”

Esther’s very voice eerily arises from the institution documents. The intact file from the 1940’s provided a breathtaking glimpse into a patient’s very unusual time at asylum, and this information is shared at times in original form, on institution letterhead, giving the reader a view into the doctor’s chamber as he interviews and writes an Abstract of Commitment for his mental health patient, and a peek at Ward Notes that detail day-to-day (but anything but ordinary) life. “Patient was asked why she didn’t go in dining room to work this a.m. and patient very sarcastic. Replied, ‘I go in whenever I can and that’s that. This God Damn place is enough to make patients sick.’” And Esther’s treatment from the institution director is most unusual. For, upon seeing her talent (and hearing incessantly from Merle Hoyleman), Dr. Alfred M. Stanley of Harlem Valley Hospital provided means for Esther to sell, as approximately fifteen letters between Merle and him attest–as well as intriguing correspondence to a Pittsburgh Carnegie Museum of Art administrator.

Secondary source documents and dialogues, no less detailed, also tell Esther’s story. The author conducted extensive interviews with twenty individuals who knew Esther. Some of these surface in a real-time fashion, so that there becomes an interesting give and take of voices throughout the book. For it became apparent that the intensity and commitment Esther placed on the creative way of life was the same as with these equally vibrant individuals. Their offerings surely contribute to the author’s aim of better acquainting the general public with an artist’s life. Letters between friends, as well, provide insight into Esther’s plight, “the stark tragedy of trying to exist on nothing.” Esther’s school records, revealing philosophies that pointed students toward finding what most speaks to one in this life, are significantly outlined early on in the book, and stressed throughout is the irony that the Carnegie Museum purchased many of Esther’s works prior to 1955, but they may still be in storage to this day. In 1992, the author brought Esther’s art to the attention of Director Emeritus of the museum, Dr. Leon Arkus, and he accurately defined her as a sophisticated independent artist with original vision, whose work, though evocative of the primitive, was “by no means naive.”

Excellent reviews of Esther’s early work in Pittsburgh are included, as is information taken from the Archives of American Art in New York about the Washington Square Outdoor Shows, a mainstay for struggling Village artists. Also woven into the tapestry of an already intricately layered design of a life is the author’s independent scholarship into the Federal Arts Projects, the Abstract Expressionists, and perhaps especially, women artists, and mental illness. The author visited the institution, taking photos and meeting with a current-day administrator who has been totally in support of this project. Scores of secondary source support of a scholarly nature are carefully integrated throughout, and the author judiciously underscores commentary with her own perspective as a former mental health professional and especially as a working creative artist for the last ten years. All of these larger issues make themselves apparent in Esther’s life; the author duly attends to them, with the end result being a story that has broad potential appeal and impact, informing and engaging readers at multiple levels.

Esther slowly lost her sight toward the end of her life. One of her closest friends from the 1950’s accurately clarifies what points toward the author’s premise–one arrived at only upon full review of the wealth of background material, then undertaking the writing of the life of this artist. It would explain having arrived at a work that seemed to write itself, a work which became more significant than a single biography. Edward Kinchley Evans felt that Esther Phillips’ blindness was a “self-inflicted sorrow wound,” essentially because the world would not view her and her friends’ work as meaningful. The author writes for many and to many more, in hope to change that view in a large way.

“Many thanks for sending your book, This Fantastic Struggle: The Life & Art of Esther Phillips to me. It is wonderful work and I am flattered that you chose to send me a copy.” –Teresa Heinz

“What a great talk! Your blend of content and process was just right! I really appreciated that you provided the audience with a context to Esther Phillips, and how your experience as an artist and working in the mental health profession connects to your role as a historian and writer. The research stories were entertaining… and your enthusiasm contagious. Thank you again for your willingness to participate in our Meet the Author series.”

–Anne Fortescue, Heinz History Center

Q & A w/ the author, 2002

How did your background lead you to write This Fantastic Struggle?

Ten years ago, I took a leap of faith and quit my 9-to-5 job as a Vocational Counselor at a mental health agency, where I developed work leads for clients with manic depression, personality disorders and schizophrenia. I decided it was time to try to make a go of it with my art. I had become fascinated at the time with the story of artist Esther Phillips, as I researched into her life on my down time, and realized I wanted to pursue the writing of a book.

I embarked on not only that project but began to fully pursue my other creative interests–writing original works for cross-disciplinary performance work, creating a body of musical works to stand on their own for solo performance, teaching children improvisation, doing studio work both commercial and for local bands, accompanying dance, and producing and directing conceptual performance pieces.

Though I actually did a variety of things post-college, and before my mental health agency job (GED teacher, career counselor, research assistant at the University of Pittsburgh., library positions), none have been as unusual or interesting as the quest to make a living as a working creative artist. Or as fulfilling.

What are some of your professional & personal interests?

Collaborating with artists of various genres, developing a sense of creative exploration in children (so they see that they can find their own path creatively), touting the call to adults to awaken to “authentic sense of self” in this life, advocating for mental health concerns which I believe touch us all at some point in our lives, and proving that artists are workers and a viable part of this society. Personal interests include playing in underground bands, and fascination with old houses like my own sitting atop a hill since 1891 and providing a view of the bustling cityscape & three rivers, with lovely backyard terraced sanctuary.

Anything unusual in the research & writing of your book?

In the finding of content matter, nothing was ordinary! Everything an intriguing exploration, a real find, which I could talk much more about. . . One technical point to mention, though, is that the first computer draft of my manuscript was on an Apple II (this was already 1995!) My generous younger brother did my next two computer upgrades for me from company hand-me-downs—first an Apple Performa and then a Power Mac. Along the way, I actually (barely) learned Netscape Composer and later no longer needed to go into the Carnegie Library to get on the internet.